It seems to depict, in schematic detail, biological, anatomical and technological impossibilities.

The Codex is a catalogue of knowledge from a world that doesn’t exist, written in a ‘code’ completely unrelated to actual language and filled with illustrations of chimerical organisms and machines. The Voynich Manuscript has often been compared to the Codex Seraphinianus, which was published in 1981 and eventually revealed to be the work of an Italian artist and designer called Luigi Serafini. The same word sometimes appears two, three or more times in a row, and there are no repeated strings of two or more ‘words’ that would signal the use of common phrases. But the ‘words’ in the Voynich Manuscript also follow patterns not found in any known language. Recent statistical analyses of the distribution of ‘letters’ and ‘words’ have shown that they possess features associated with natural-language texts, such as conformity with Zipf’s Law, which states that words are distributed along a curve such that the most frequent word appears about twice as often as the second most frequent word, three times as often as the third most frequent word, and so on. Someone must have cared a great deal about this book to see it through to completion. However many there were, the manuscript is clearly the result of many months or years of effortful labour. Subtle variations in the handwriting suggest the work of at least two and possibly as many as eight different scribes. One of the most compelling clues discovered in the manuscript also points toward northern Italy: a tiny drawing of a castle with ‘swallow-tail’ or Ghibelline fortifications unique to the region.

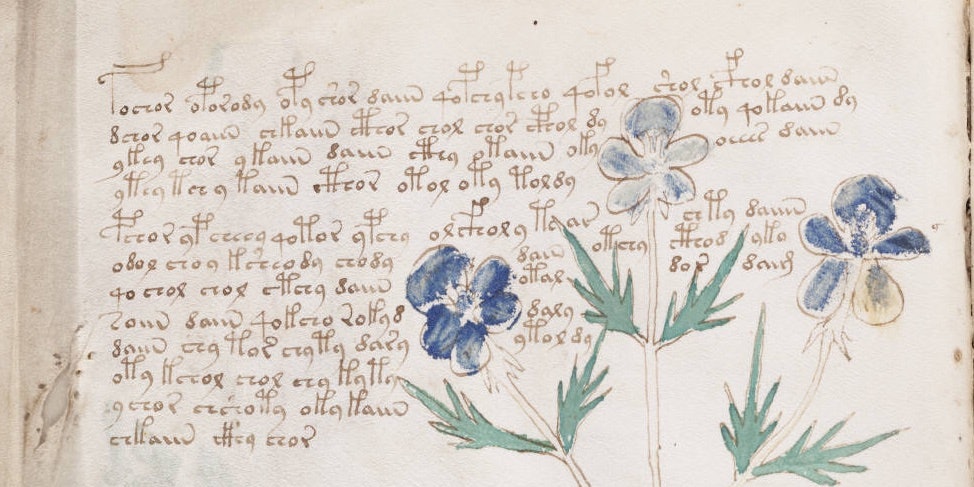

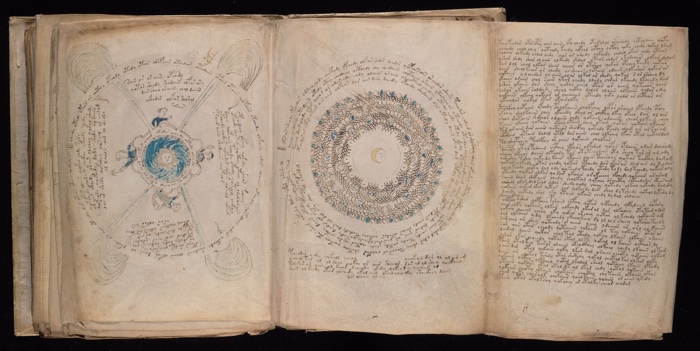

Some have noted similarities between these symbols and ones found in codes used in medieval Europe, particularly northern Italy, where city-states would transport messages by horseback along routes where bandits were common. These seem to be arranged into words that run from left to right and are grouped into paragraphs, or appear as labels attached to the drawings and diagrams. The glyphs of the unknown script are looping and lovely (one set is known as the ‘gallows’ because of the characters’ resemblance to a hangman’s scaffold), making up an ‘alphabet’ of some thirty symbols. This does not rule out the possibility that the drawings illustrate heretical descriptions of female contraception or abortion, as some have suggested – subjects that may have warranted the use of careful code. The artist who illustrated the Voynich Manuscript had a heavy hand, but the appearance of the bathing women may simply reflect artistic convention and gender norms. But visual representations of the female body in medieval Europe routinely featured rouged cheeks and a rounded belly, as with Botticelli’s Venus or the female figures in the paintings of Lucas Cranach the Elder. Many have suggested that the bathing women look pregnant, which could indicate that this is a medicinal text concerning women’s health or fertility cycles. The vellum pages have been carbon-dated to the early 15th century, and the inks were created with materials and processes common in the late medieval period. But in the Voynich Manuscript most of the bathers are female and ‘their postures and activities have no clear parallel in alchemical writing.’ Trying to interpret this book as an alchemical text soon becomes a maddening game of guesswork and association. As Jennifer Rampling notes in an essay in the new Yale edition, alchemical treatises often included figurative and allegorical representations: ‘The “chemical wedding” of solar king and lunar queen might represent the alchemical process of conjunction – the physical joining of gold and silver – or suggest an analogy for the mysterious and unseen bonds between substances, now envisioned in terms of human desire.’ Naked men and women, sometimes pictured in hexagonal stone baths, were used to represent substances undergoing dissolution or conjunction. Take the naked women of the ‘balneological’ section. But as we lack context for them, we can’t tell what they are supposed to represent. The drawings – faces embedded in leafy vegetation, plants waving tentacular arms, tubes bulging like human organs – look as though they could be illustrations for a compendium of natural science. The manuscript’s main sections are known to scholars as the ‘herbal’, ‘astrological’, ‘balneological’ and ‘pharmacological’ – the list of recipes, if that is what it is, comes at the end – and many readers have attempted comparisons to medieval codices of botany, astrology, alchemy and materia medica.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)